Brian Orser: We All Speak the Same Language of Figure Skating

The last spin ends amidst cheers and yells. In the centre of the rink stands one of the top skaters in men's figure skating field, gasping for air, surrounded by all the coaches, choreographers and athletes from Cricket Skating and Curling Club. Another skater comes to the ice, while the rest continue to cheer for him—'Come on! Push, push, you can do it!' Orser's eyes sparkle with excitement when he is describing the atmosphere in the Club. 'Everyone is helping each other. Normally it'll be easy just to stop, but everybody's clamping for him. He's grateful that we got through that first one. Then we do it again.'

From Orser's point of view, run-throughs are real tests. 'When you first start doing run-throughs, it's gonna be really ugly. You have to get into the trenches in this type of work. Bit by bit, day by day, week by week, the programmes get better. Then we work on sections. We have a different method, and it seems to work.'

While some Russian and Chinese coaches avoid overburdening their skaters with run-throughs, Orser and Tracy Wilson, the self-proclaimed 'old-school' North American coaches, believe in run-throughs. Yet he tries to make sure they are not too Spartan. One solution is to do run-throughs without doing big tricks. Jumping a triple Salchow instead of a quad Sal, the skater adapts to the same physiological system, but the risk of injury reduces. Then he may ask his skaters to focus on the second half with usually easier jumps, although, in the case of his top skaters, the word 'easier' can mean a quad, two triple Axels, five jumps in total.

This kind of run-through does not last for the whole year. In the spring time of May and June, the Cricket Club concentrates on skating skills, practicing a lot of stroking without doing jumps or spins. The aim is not only to train skaters to fly across the ice, but also teach them how to cross one foot over the top of the other, and how to get the blade to accelerate. When time comes that they should practice spinning, he also teaches how to maximize the spins without having to work too hard. Afterwards, they add the new choreography to their practice schedule, getting familiar with new transitions while going on to polish skating skills. In summer, when the skaters are in good shape, they focus on new jumps, including new quads. The run-through starts halfway through the summer and is subject to everyone's schedule. Those whose competitions start earlier do run-throughs ahead of others. Orser wants his skaters to peak at the right time. His philosophy is that you have to push the skaters, chase them a little bit, but not train them too much.

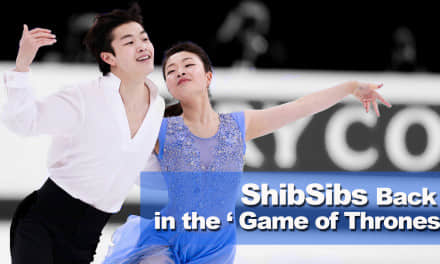

(Photography by Zhong/SkatingChina)

With the assistance of Tracy Wilson and other experts, Orser is ambitious to produce a whole package. 'Competing as a senior, you have to fill up the ice. You have to go fast. You have to have those Patrick Chan deep edges.' Great jumpers like Hanyu and Fernandez are now working arduously on skating skills and transitions. The typical difficult entries into quads apparently make their jumps less consistent for the moment, but Orser is confident in the benefits they bring. 'As soon as the new (scoring) system came on, I embraced it. I tried to figure out the best wisdom to get the most points.'

He feels less challenged than amazed by the Chinese wonder boy Boyang Jin, who a couple of days ago just landed quad Lutz-triple Toeloop combination in the short programme, attempted four quads in the long and eventually landed three (though there were weak landings). Jin's entries into his alien jumps were earthly, and he earned around 7 points for transition. Still, he posed a threat to the reigning World Champion at Cup of China, losing by less than 10 points. Brian would like his skaters to watch new talents like Jin, for it keeps them competitive. In the meantime, he boasts certain qualities of his own protégés. 'Javi and Yuzu have a little bit more maturity. We do capitalize on the transitions, but also on the elements where people can win and lose competitions, it is in the GOEs. So you need to do your own elements really well, including spins, steps, choreo steps. That's really where it makes a difference.'

Orser has good reason to feel confident. When Javier Fernandez came to Toronto in 2011, he was, in Orser's words, 'sloppy, out of shape', earning Level 1 or Level 2 for his 'terrible' spins. In just a few months, his component scores rocketed at Skate Canada. Brian is surprised on hearing how much he improved (16 points, contrasting Skate Canada with Worlds 2011), and attributes it to their patient work with Fernandez and good choreography of that season. The coaches 'smothered him with care', but polished him step by step, not dumping out information all at once, in case he should lose interest. After all, the Spaniard was a well-known lazy talent then. It was only when he lost his government funding and had to pay for his lessons that he treasured every moment on ice. 'I think it's the best thing that ever happened to him that now he was accountable for every dollar he was spending'.

Nam Nyugen, a rising star of Cricket Club, who sat in the fifth place at 2015 Worlds, is just on the same track. Armed with consistent jumps, these days the young Canadian champion has been training mostly to improve his spins, and also been planning to strengthen his transition in the near future. Yet Orser is patient with his growth as a skater and as a man. 'Yuzu and Javi took a long time. Nam needs to mature physically in order to do that.'

Speaking of the young Korean pupil Jun Hwan Cha, Orser is visibly appreciative. Having met and talked with him in a previous competition, Orser admitted that he was intrigued by Cha's techniques and genuine expression of his choreography, which was coming out of his body. 'Even though he's only thirteen, he really does skate like senior. I haven't been this excited for a long time.' The young boy broke his foot in the summer, but won the Autumn Classic Junior in October.

They have the potential, and the coaches trust them. Orser thinks his own reputation as two-time Olympic silver medalist would not make the judges trust his disciples. What makes a difference is that the skater delivers and comes up with something fresh. He thinks himself tough with the skaters. In the private rink, the situation can turn ugly when they do not deliver. 'I'm not always this nice. But Javi … And the same with Yuzu. They can get it and respect that approach.'

Despite the high technical criteria Team Orser is pursuing, the coach proposes passion as the most significant quality for a good skater. He teaches other skaters who will never be big champions as well, and enjoys their skating because they love to learn and express themselves, and that they are dedicated to skating. Once in a while, he sets up exercises for the skaters and looks at them in his office, finding them working hard even on their own. He feels fortunate with Yuzu, Javi, Nam, Elizabet just for their commitment, something that cannot be taught through lessons. Respect for everyone and communication are also crucial qualities. Orser likes to teach his athletes to be good people and have good manners.

(Photography by Orange/SkatingChina)

Coaching an international group of pupils, Orser does not see the barrier to communication. 'We all speak the same language of figure skating. I really do work with body language. I can show them stuff because I am still very active on the ice.' At the very beginning, there was misunderstanding with Hanyu. 'For example, I say “I would like you to do three more Lutz” and he does a triple flip, and I say, come back, and we make sure it's clear.' It is no longer a problem, since Hanyu's English is getting better, and Orser has found a way to instruct with more clarity and efficiency.

Orser thinks it necessary to understand different cultures of his pupils. Coincidentally, Fernandez and Hanyu both choose to exploit their national cultures this season. Orser did not involve in their musical choices. He takes their choices to be smart, but mentions that 'you have to do it at the right time'. A couple of years ago, he saw on TV a guy reminiscent of Fernandez, a Flamenco dancer of some contemporary school. He considered waiting for one more year until the Spanish skater was able to dance Flamenco, and this is the right year. Hanyu's 'wa' programme is relatively obscure for the Canadian coach, who interprets the protagonist, the 'onmyoji', as a warrior or samurai. Yet he placed his trust in the choreographer Shae-lynn Bourne, and she researched with Hanyu on Japanese Noh theatre. What they have come up with, Orser believes, is 'not just skating to music, but interpreting what is appropriate, doing the proper movement.'

It is the second programme Bourne has choreographed for Hanyu. Orser thinks it helpful to cooperate with the same choreographer all the way through, and the club has benefited from a long-term collaboration with choreographers such as David Wilson, Kurt Browning and Jeffrey Buttle. However, exploring new styles is also crucial to the growth of a skater. In the first year of his training in Toronto, Fernandez, rather 'shyly' (probably because he thought it was not his old self), suggested doing a Ballet piece. In the end, the team forged the Verdi medley, a programme that maintained typical Fernandez humour and had more depths than the youthful Pirates of the Caribbean. 'Every season, we're learning more and more and more what his potential is.' This may say something about Orser as a coach.

前往 中文版

(By Heloise Xiao)

近期评论

——“花样滑冰是艺术与体育最好的结合”

——“花样滑冰是艺术与体育最好的结合”